The best stories and poems are the ones that draw us in through the expert use of words. We love descriptions and expressions that make us feel we’re there experiencing life in the imaginary world along with the characters. Sometimes, however, figuring out what writers mean is a little more challenging. That’s because sometimes authors use words in ways they’re not normally used, and readers have to interpret them, almost as if reading a foreign language.

There are a few different definitions of ‘figurative language’, but all point to the same thing: figurative language refers to a specific type of language we use to heighten a reader’s experience. Ordinary statements take on a whole new life as we move from literal, exact meaning to abstract, creative meaning.

Pigs strap on jet packs and soar through the sky like eagles on steroids. Pampered pet pooches perch precariously on painted points. Then, BLAM! You’re a rooster in a rainstorm, soaked through to your bones! Nothing is as it seems.

The list of literary devices used as figures of speech is longer than most people realize, with the number going upwards of 20. The good news is that we often use various types of figurative language without knowing what they’re called, and the even better news is that there are only about 6 or so common ones that we should be familiar with.

1. Simile

2. Metaphor

3. Personification

4. Alliteration

5. Hyperbole

6. Onomatopoeia

Simile

This is probably the most common type of figurative language. We’ve all encountered expressions and sayings like: “as busy as a bee”, or “as strong as an ox”, and even “as stubborn as a mule.” Some similes also use the word ‘like’, for example “They fought like cats and dogs” or “That show was like watching paint dry.” A simile is a comparison. You’re comparing a specific quality in one item, with a similar quality in another item that people are familiar with. For example, paint takes some time to dry, and it’s not the most exciting thing to look at. Guess what we’re saying about the show? Yup, it’s boring and slow.

Personification

We do this with our pets all the time when we assign human attributes and thought processes to their behaviour. “Cats are devious animals trying to take over the world.” Sometimes we even assign human characteristics and intentions to inanimate objects. “I swear that spoon was trying to kill me!” Anytime we add human meaning to the actions of non-human creatures or objects, we’re using personification.

Alliteration

This one uses our fascination with sound to create peculiar and interesting reactions. By repeating initial consonants, we create tongue-twisters and amusing statements. One of the more famous expressions of alliteration is: Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers. It’s fun to create your own too, especially if you use words that would not normally come together in a sentence and still try to have the sentence make sense.

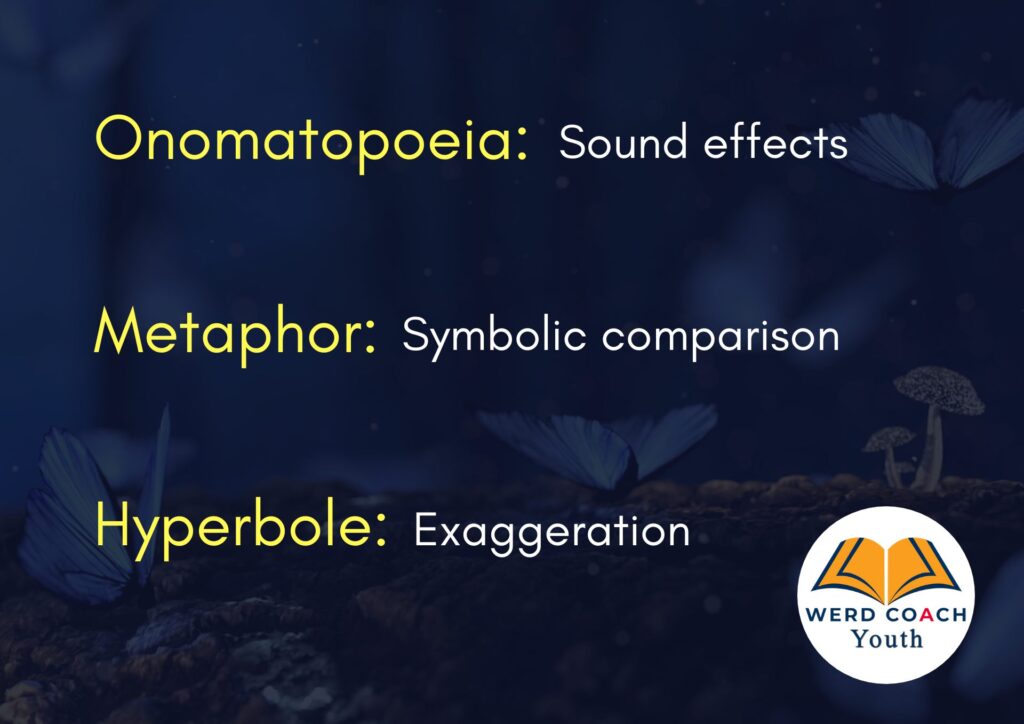

Onomatopoeia

This one is a favorite of mine for two reasons. First, the word itself has to be one of the coolest sounding real words in the English language. Say it out loud three times fast and you’ll understand what I mean. The second reason I love this type of figurative language is because of what it is. There are times in writing that you want to conjour a feeling in your audience and conventional words just don’t work well. Enter the word that sounds like the noise you’re describing! How else can you describe a whooshing wind, or a tinkling bell, or the sound of a closing door? Doesn’t BLADAM give you a different response altogether from SLAM or CLICK?

Metaphor

This one is related to similes because it is also used for making a comparison. A metaphor can be considered a simile that has been intensified or strengthened. Instead of saying the two things you’re comparing are similar, like or as, you remove those words to say that the two things are each other. So, instead of “roaring like a lion” you’re now “a roaring lion”. And instead of being “hungry as a bear” you’re now “a hungry bear”. The comparison is the same, but writers are now saying that it’s more than just a similarity, the behaviour is so strong the two things might as well be the same.

Hyperbole

Parents and teachers are often guilty of using hyperbole with children, “I’ve told you a million times to clean up your room!” or “Why do you always ask that question?” These exaggerated statements are not meant to be taken literally, but are meant to highlight something. So, I may not have told you a million times, I don’t actually know because I haven’t been counting, but it feels like a million because it’s quite a lot and I’m tired of saying it.

When writers use figurative language, they’re saying one thing when they really mean something else. This is one of the reasons many people have trouble understanding the meaning associated with some expressions. While many are so common they’ve become integrated into our system of language as idiomatic expressions, many writers create their own, and that requires some thinking on the reader’s part.

The first step in being able to decipher figurative language is to understand the various types there are. For SEA, those described on the other photos in this post are the main ones children need to know. Make sure they know the definitions and are able to recognize examples.

In addition to reading many different types of texts in which figurative language is used, have kids create their own. Encourage them to have fun with this, to make up the craziest, or wackiest metaphor, hyperbole, onomatopoeia, personification, alliteration, or simile.

One word of caution, however. Children should be reminded that when they are in the role of writer, the language they use should be reasonable and understandable. In other words, readers should not feel exasperated trying to figure out what they mean. At this level, readability is paramount.

To teach recognition of figurative language in a fun way, children can play matching games where they have tabs with sentences and tabs with labels they must match. They can work in groups or on their own.

To add some movement into the mix, children can play a twister-style game with the figurative language. Circles can be drawn on the ground, each labeled for a type of figurative language. The teacher reads a sentence and students have to touch the circle that correctly identifies the example with either a hand or a foot. For example, if the teacher says, “He’s as slippery as a snake. Right hand.” Then the children would have to stretch to touch the circle labeled ‘Simile’ with their right hand. There should be several circles labeled ‘Simile’ to choose from. This is ideal for groups of 3 or 4 children.

A modification of that game for larger groups would have larger circles drawn and labeled, and children have to run to the circle they think is the correct answer. Incorrect answers can be monitored and corrected, plus a winner could be determined. After three chances of incorrect answers, a child would be out of the game. Those who have the correct answers remain. A single winner or group of winners could emerge after several rounds.

For children who love art and play dough, these activities can also be integrated into a lesson on figurative language. After discussing and practicing with one of the literary devices, ask the children to select one sentence from a list given, or write their own, and create a piece of art to illustrate the sentence. They can paint, draw, use play dough, or any other material they have at their disposal. Afterward, each child would need to explain their concept.

Teaching figurative language is an opportunity to have a fun and exciting class. What other ideas can you think of to make your lesson enjoyable?