After looking at figurative language last week, you probably realize that sometimes words don’t follow the rules. Even if you have a dictionary and can look up the definition of a word, you could still have a hard time figuring out what the word means in a reading passage. Enter “context clues” to save the day. This post explains what context clues are, how they help readers decipher the meaning of words and phrases without a dictionary or outside help, and how to get others using context clues effectively.

When we read, we sometimes come across words we don’t know. This is a great way to build vocabulary, especially if you have the internet or a dictionary at hand to tell you the meaning of the new word.

But we don’t always have that luxury, especially during an exam. It can be intimidating when we’re asked “What’s the meaning of X-Word” and that’s the first time you’ve seen “X-Word.” Some readers shut down, some panic, and the meaning of the passage is lost, all because of one word.

Sometimes, however, writers are aware that they’re using words readers might not be familiar with, and they helps us out by giving us clues to the meaning of the word right there in the passage. These clues are called Context Clues because they’re found in the context of the passage.

The thing to remember about context clues is that they’re not always in the same place.

Some context clues are found within the same sentence as the new word.

Some are found in the sentences before or after the one with the new word.

You can even figure out the meaning of a word by thinking about how the word is used in the sentence, whether it’s a noun or verb or adjective.

The trick is to always remember that context clues exist. Once children remember that they can get help with vocabulary words right there in the passage they’re reading, they won’t feel as anxious when they come across a new word. It’s all about building confidence by teaching strategies.

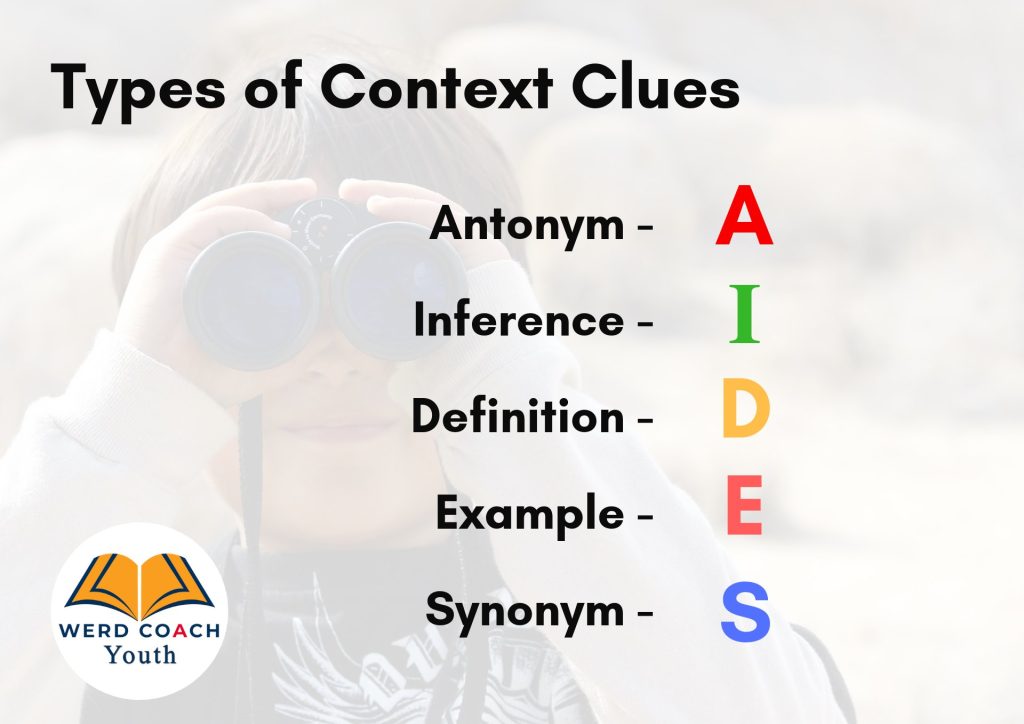

There are different types of context clues, and one way to remember them is to think of them as AIDES. Since context clues aide our understanding of meaning in a passage, this acronym is a good fit.

A – Antonyms. Sometimes, writers give us the opposite meaning of the word. Example: Our new teacher is cranky and unapproachable, but our last teacher was affable. The word ‘but’ indicates contrast, so we know affable is the opposite of cranky and unapproachable.

I – Inference. Sometimes the meaning of word is implied and meaning is derived from reading the sentences before and after. Example: My blouse is torn. When I pulled it over my head, it got caught on my earrings. In this sentence, there’s an explanation of how a blouse is used so you can guess it’s something you wear like a shirt.

D – Definition. Example: Sedentary individuals, people who are not very active, often have poor health. In that sentence, the word sedentary is defined. Usually, definitions are put within commas, or come after words such as ‘refer’, ‘be called’, ‘may be seen as’, or ‘which is’.

E – Example. Sometimes an example of the word is given, and this helps in figuring out what the word means. Example: She likes contact sports; for example rugby, football, and martial arts. From the examples given, we can guess that contact sports are those in which players get into physical contact with each other.

S – Synonyms. Sometimes writers use other words that have similar meaning to the new word. Example: Elephants are enormous. They are the largest land mammals. In this case another, more familiar word is used the same way the word enormous is used. By looking at the two sentences, we can guess that ‘largest’ means something similar to ‘enormous.’ They are synonyms, so ‘enormous’ would mean something large.

The main thing with teaching context clues, is to get children to understand that there is help with figuring out the meaning of new words. Many children get anxious when they meet words they don’t know, and don’t even try to figure them out. They either ask someone to give them the definition, or they check their dictionary, or they give up and skip the word altogether.

So, when teaching context clues, let children know that this isn’t a test in itself, but a way to help them when they’re reading and doing comprehension questions. Explain that “I don’t know” is not a suitable answer to “what does that word mean”. They should always try to figure out the meaning for themselves before checking the dictionary or asking for help.

One way to make this fun is to make it a game. Whenever doing comprehension exercises or reading and children come across a word they don’t know see who can figure it out first. Keep a tally of points and at the end of a set time period, the person who gets the most points wins. There need not be a tangible reward, just bragging rights as the person who figures out context clues.

As an added incentive to get everyone involved, have them work in groups and the group gets the points only when everyone has the correct answer. Make it so that the same person can’t always give the answer, and every time an answer is given it must be accompanied by “I figured out that meaning because…” So the person giving the definition must say how they came up with the answer.

For those students who are tactile learners, you can work ahead and identify words in the passage that may be challenging. Write or print easier synonyms that the children would know. Give them the synonyms and let them know that while reading they may come across words they don’t know. The meanings are on the slips and the context clues would help them know which words are the right ones to substitute. This gives students something to manipulate and move around while they’re reading.

The more children use context clues, the more at ease they will become with using them. This means such exercises should be done often. Skill development in this area is essential for faster reading, better comprehension, and reduced anxiety.